Delivered on the ocassion of The Mark Cousins Memorial Symposium, held at the Architectual Association on October 8, 2021.

I don’t think I can begin to tell you exactly what the Gesture is, partly because at least one of its qualities seems to be that it resists the specificity that is necessary for description, and also because I couldn’t match the eloquence with which Mark moved around the subject to formulate a performed understanding of what it could be. But instead I will tread with more humble steps and talk to you about what I see as one of its consequences to explain something of, in our artistic efforts to capture it, what it is not, and in saying what it is not we might get a little closer to what it is. How the matter of being human – that for Mark is essential to the Gesture – becomes a matter of space, so we can posit that the essence of gesture is spatial.

In the process of lost wax casting, which is probably the oldest method of casting metal for jewellery and other objects, we have the arresting of a moment in the life of the original wax object from which its replacement is cast in metal. It is this concept of arresting, the grasping of that which is really only fully comprehensible in movement, like a snap shot. It is mostly an attempt to contemplate how one ends up inhabiting a space once there is nothing more to capture. Actually, it’s not that there isn’t anything more to capture. But in the process of sculpting there inevitably comes the moment of deciding that the work involved in sculpting the object is done. The form, made of wax, is then encased in another longer lasting material, molten metal is poured from a crucible into the casing, and while the wax disappears from the mould by the process, often quite literally, the space it occupied remains. Hence the term lost wax. The void left within the cast becomes the most important thing. It leaves us the impression of that which once occupied its space, and that space inextricably belongs to it. What remains after the wax is lost to us is the space of the disappeared, and now lost, object. While this is a momentary impression that contains the very absence of movement, or the very absence of gesture, it is the capturing of an instance that it had once been. In this process, the space of occupation and absence are interlinked, actually they are inseparable. Much in the same way that Mark described in the 19th century some people were going through the solid material in Pompeii and found holes that enabled them to cast what was inside although they didn’t know what it was that they would find. They found the forms of once living beings. He talked about how the gesture can only be understood in movement, and an instance of that is taken in this type of occupation once the movement has given way, once the decision that the work can cease has been made, either by nature or by a conscious decision to stop… Gesture, he says, is being only human. Perpetually slightly out of reach as it resists description. Indeed, for all our many artistic efforts, the very place where it is captured seems to be the very place where it is not.

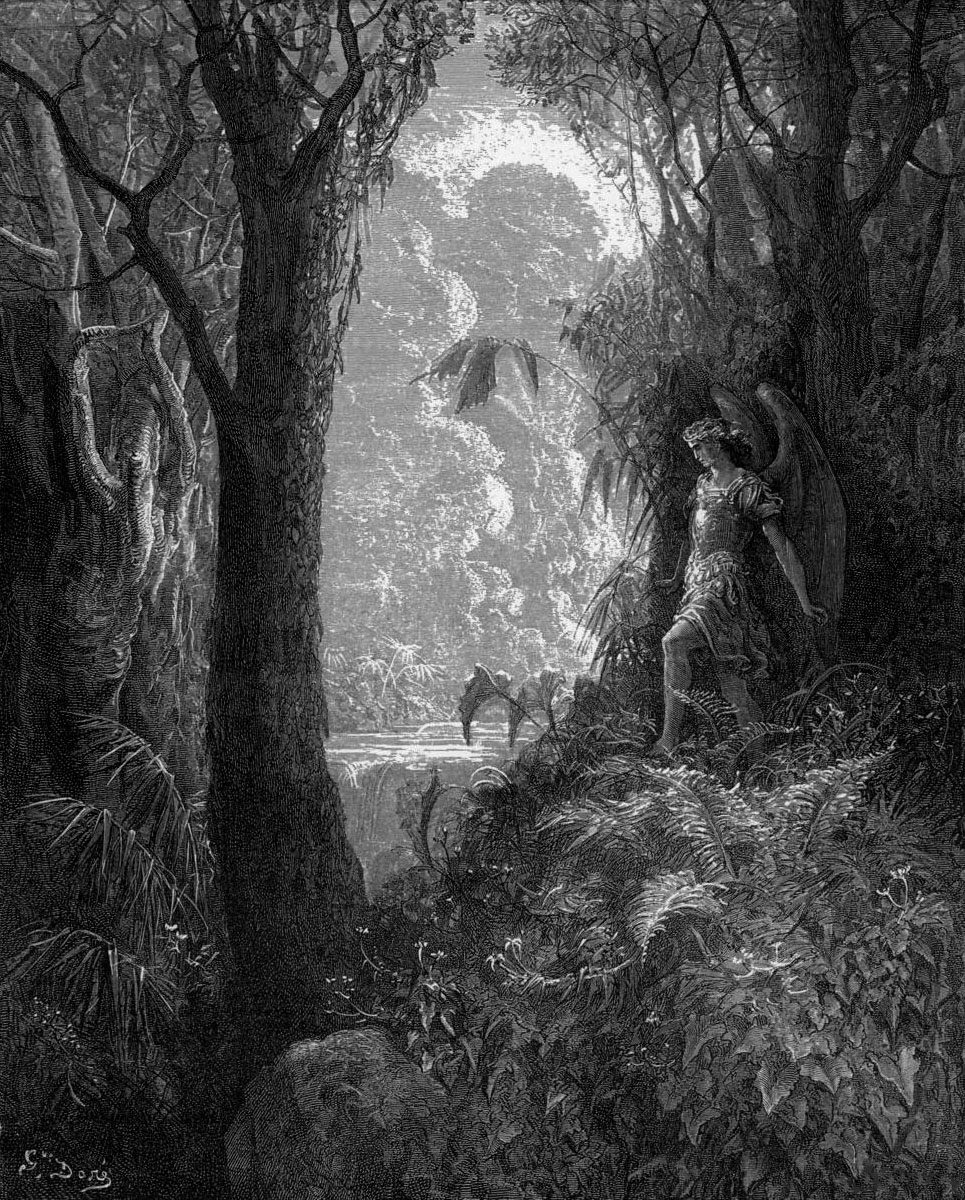

In the period after Mark physically left us, I think I was not alone in feeling his presence very strongly, very much through the fact of his absence – he also had assumed a sense of that digital ubiquity he bestowed upon Angels, not entirely out of place as the last time I remember seeing him was not in person but via my computer screen. Seamlessly transposed.

Then the news of his passing came. Everywhere and nowhere at the same time, but not somewhere anymore. It didn’t occur to me what that might mean at the time. In some ways he felt more present than he had ever done, which may well seem paradoxical but when we think of it in the following terms it seems to me to be less so. There is an idiom that we have in the Persian language that goes – jā-ye shomā khālīst / جای شما خالیست, the literal translation of which is “your place is empty”, commonly used to tell an absent person that one wishes they were here. It’s interesting to me that a person, a form, can continue to occupy a place through which the very absence of their presence is made comprehensible, just like lost wax casting, just like Pompeii, and also that this area of occupation can end up being tied to something, someone, specific. All the while they themselves may be visually subtracted, they are not, and perhaps even cannot be, spatially subtracted from the place they inhabited. This place remains theirs, linked to them, without it ever having the impossible, but none the less desired, quality of being them. We know very well what is lost.

In the months following his death, when I would talk to people about returning to the school, at 36 Bedford Square, we wondered how we would feel being back in the spaces that he occupied without him physically here to occupy them. The school, the room, the lectern, remain empty. Hollowed out, unfilled, ambivalently tied to the fact of his presence, but, only through the fact of his absence.